Helping Democracy Think

My time as a Visiting Professor at Caltech went quickly: I’ve moved back to San Francisco and had fun hiking again in the hills near Muir Woods. I’ll miss my friends and the students at Caltech, but it’s exciting to be back, ready to finish my book, ready to start my new institute and help address some of these critical global challenges.

While at Caltech, I kept thinking about differences between the type of thought needed in the academic environment, and the type of thought needed to address the broader challenges of the modern age. In many ways, scholars in academia have a better prospect of making steady, reliable progress. They can focus on a small part or single aspect of the world. They pick a problem that the mind can manage, and their ideas often are shared with (and judged by) other academic experts with a similar background.

But it’s harder for anyone working with the type of Zone IV challenges mentioned in my previous posts: Ideas here still need to retain some real meaning and substance, yet they also need to encompass a larger view of the world AND need to be formulated in a way that allows them to be shared with a broader public.

But there’s a painful irony here: Given the rough and tumble world of politics, these harder, global problems often get less careful, deliberate attention. Elected officials are so busy that they must rely on their staff. And staff members rely on policy reports, and these reports, in turn, depend on advice from domain-specific experts. But many of these Zone IV problems – concerns about global warming, about the financial system, about health care, etc. – are so hard and so open-ended that they transcend the “field of view” accessible to any given expert. There are challenges when ideas get shuffled around like this, and when proposed legislation is so complex and so full of jargon that it’s hard to read and evaluate.

We can see these challenges, for example, with the Dodd-Frank Act (passed in 2010) that was designed to help regulate the U.S. financial system. This bill is so long (848 pages) and so complex that it’s unreadable – indeed, it’s unthinkable. (I know, as I bought a copy and tried.) A bill with this level of complexity leads to a kind of pretense and charade that undercuts the very foundation of democratic governance. When ideas do not fit in mind, there’s no chance for meaningful thought, no way to cast a meaningful vote.

So, I ask: Is there, perhaps, a better way of addressing these Zone IV challenges? Do complex problems of the modern age always require such complex solutions? Or is there some chance to work at a deeper, more strategic level – some way to maintain human comprehension and control, some way to ensure that the largest, most fundamental choices are made correctly?

Yes, I think we can do a better job. As I argued when teaching at Caltech, there are cases in which deep thought – like that used when drafting the U.S. Constitution – can give a fresh perspective and lead to a better plan. It can help us move beyond stopgap solutions and thus start with a more solid foundation.

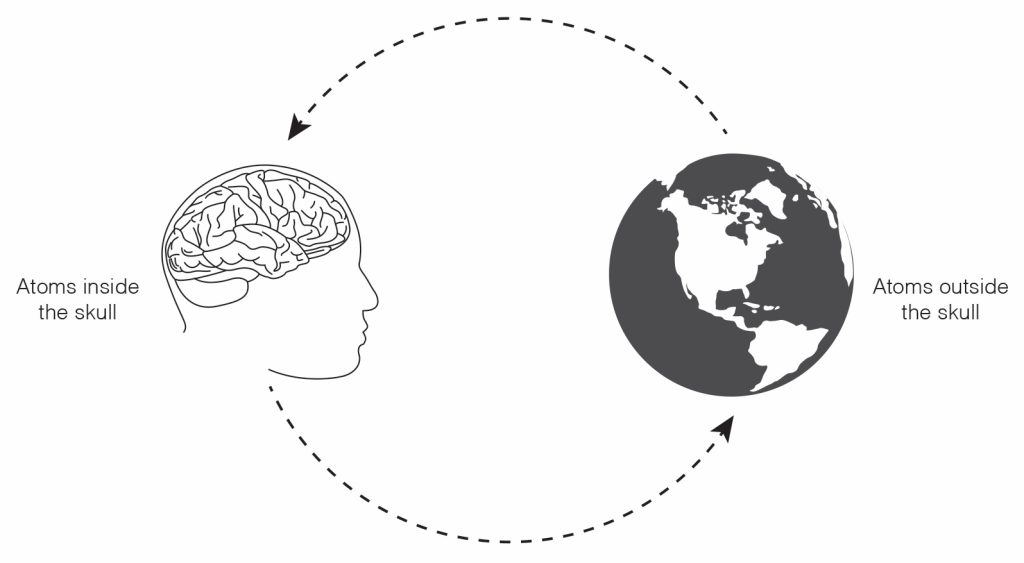

My upcoming book will offer a few examples showing how deep thought can help, but my analysis of the economic and financial system – worked out over several years of study – is summarized below. Beginning with the basics, let’s note: we’ve moved beyond the barter system, but we’re still as dependent as ever on a flow of physical events for food, clothing, shelter, transportation, entertainment, and everything else. And we remain just as dependent on others, just as dependent on community, as we would be in a barter system – it’s just that we now track “contributions to” and “withdrawals from” this shared public realm via the use of money.

In outline: You can get paid if you bring something useful to this public marketplace; you pay money if you want to take something home.

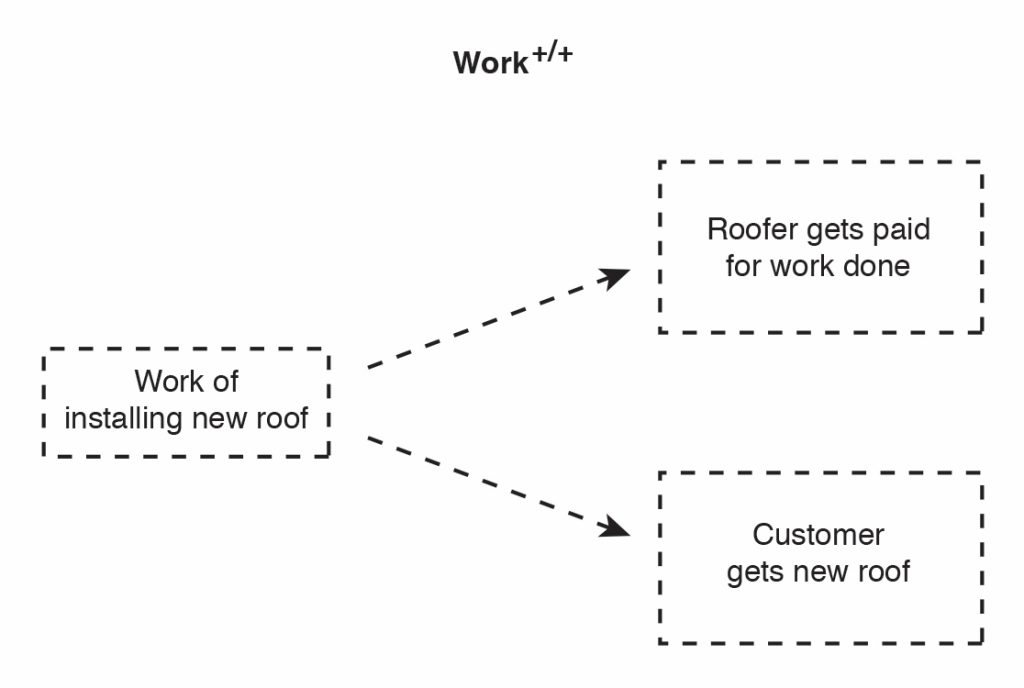

I describe this basic, mutually beneficial pattern as one of “work+/+”. Let’s take for instance, the summer job I once had as a roofer. There was a simple bargain here, a simple “social contract”: I got paid only as I left a favorable physical residual for others. I was happy to have the money, and the homeowners were delighted to have a new roof.

And the real failure of the Dodd-Frank Act starts right here: It’s written as if the overall stability of the financial system were the only issue of concern to the government. The bill fails to consider these other, equally fundamental aspects of the social contract. It fails to consider that much of the risk to stability, and much of the public anger and cynicism about government bailouts of banks, arise because mutually beneficial patterns of work+/+ have been replaced by parasitic processes of work+/- (described below).

There are many such parasitic processes in the modern economic/financial system – many ways to take money off the table without leaving any residual benefit for others. (See, for example, John Cassidy’s 2010 article in The New Yorker entitled “What Good Is Wall Street?”)

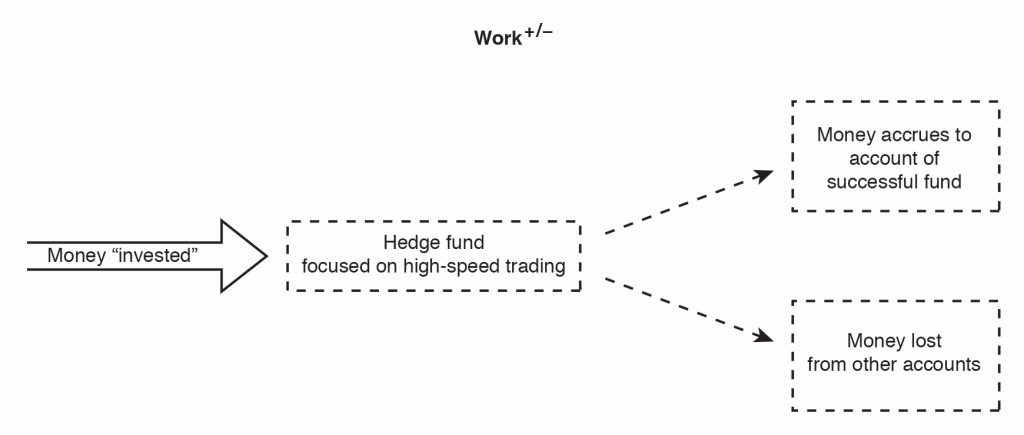

One of the most obvious forms of work+/- involves high-speed trading of stocks, commodities or currencies, and a prototypical pattern is illustrated in the diagram below.

Nothing is created here; nothing is left behind that would be worth so much as a crust of bread in the barter system. Hedge fund managers simply try to take advantage of vagaries in pricing, and their profits come at the expense of other traders who move less quickly. And it doesn’t really matter whether the holding period here is seconds, minutes, hours, or days. This type of “investment” never lasts long enough to offer any real benefit to the company – never allowing them to hire a new employee, buy new equipment, open a new plant, etc.

Other schemes for work+/- include ways of “shorting the market” (profiting as the value of a stock falls), many ways of using “financial derivatives,” and investment banking schemes that take a big fee before waiting to find out whether the reorganized company actually works more effectively.

The net effect is that work+/- need not rely on, and need not facilitate, any actual progress of the underlying economic system. It doesn’t need any forward progress of the economic engine. It can extract money from the fluctuations, the vibrations – it can make money as the engine spits and splutters.

It’s worth noting that a work+/+ transaction (deemed favorable by the two parties involved) can have unfavorable system-level consequences for others. Thus the purchase of a pack of cigarettes supports an industry that may entice young people to take up smoking, and the work+/+ transaction involved when filling my car’s fuel tank will contribute to the problem of global warming. And yet, trying to frame everything in terms of work+/+ at least helps us clear away part of the problem and begin to see who, if anyone, will benefit. Everyone on Main Street needs to struggle to survive in a world of work+/+, while much of Wall Street can siphon off the money through schemes for work+/-. Adam Smith would be appalled at the way this invisible hand is so often busy picking someone else’s pocket.

I’ll discuss these ideas in more detail in my book – 1) summarizing the risks to society – including risks of complexity and instability – that arise with these new schemes and then 2) proposing changes to the tax law that could lead everyone to focus on work+/+. Our failure to regulate these parasitic modes is a critical problem for society, but I also use this example to make a more fundamental point: There are times when careful thought allows us to reframe problems in ways that will help democracy think more clearly and that will let more people participate in the decision-making process. This helps control complexity, producing ideas that:

1) give some adequate description of the world, and outline some useful plan of action, and yet also

2) fit readily in the human mind.

In a system of democratic governance, we desperately need this new kind of currency, this new denomination of thought – ideas that are simple enough to fit in the human mind, yet powerful enough to change the world and help maintain a livable human future. This new path, this via sapiens, gives fresh hope for humanity in an age of complexity.